China’s unfair ‘overcapacity’

by Michael Roberts, MR Online, April 18, 2024 - The recent nonsense issued by U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen on China’s ‘overcapacity’ and ‘unfair subsidies’ to its industries is particularly pathetic. As Renaud Bertrand put it:

The so-called threat of China’s ‘industrial overcapacity’ is a buzzword that actually means that China is simply too competitive, and by asking it to address this, what Yellen is truly asking of China is akin to a fellow sprinter asking Usain Bolt to run less fast because he can’t keep up.

Indeed, let me quote Bertrand’s rebuttal of Yellen’s claims of ‘overcapacity’:

Let’s start with capacity utilization rates. It’s crystal clear they’ve been pretty much constant in China for the past 10 years, standing at roughly 76% right now, which is in the same ballpark as America’s own utilization rates, at about 78%. So, there’s no issue there.

Bertrand goes on:

Despite the very low prices for its EVs or solar panels, Chinese companies involved still make a profit (industrial profits are rising at double-digit growth), and they DO charge higher prices abroad than at home. The competitiveness of Chinese companies is overwhelming: today, in scores of industries—like solar or EVs—there is simply no way for American or European companies to compete with Chinese ones. This is the real issue: Yellen and Western leaders are afraid that if things keep going, China will simply eat everyone’s lunch.

China is the only country in the world that produces all categories of goods classified by the World Customs Organization (WCO). This gives it a key advantage when it comes to end prices: when you want to build something in China, you can literally find the entire supply chain for it at home. Bertrand:

China has become an innovation powerhouse. In 2023, it filed roughly as many patents as the rest of the world combined, and it’s now estimated to lead 37 out of the 44 critical technologies for the future. All this, too, has implications when it comes to the final prices of its products.

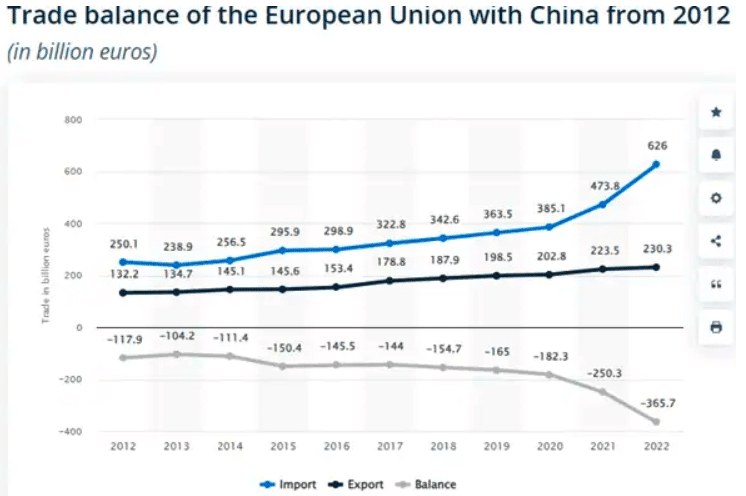

Europe’s leaders have been echoing Yellen’s claims. After meeting Xi in Beijing last December, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen noted the EU’s trade deficit with China had ballooned to €400bn from €40bn 20 years ago, as she highlighted a series of complaints, including China’s industrial ‘overcapacity,’ she said:

European leaders will not be able to tolerate that our industrial base is undermined by unfair competition.

But let’s get this right: the EU trade deficit with China has risen from $40bn to $400bn in 20 years! Not two years, not five years, not ten years, but throughout this century. First, that makes the rise in the deficit not so large per year, say about $10-15bn, and throughout that period, we heard little complaint from the EU that China was adopting unfair trade practices. Suddenly, after the debacle of rising energy costs after cutting off Russian energy imports and a virtual two-year recession in the major EU countries, von der Leyen now blames China. Indeed, most of the increase in the ‘China deficit’ has come in the post-pandemic period.

As for the U.S., currently, the bilateral trade deficit between the U.S. and China relative to the size of the U.S. economy, is the lowest it’s been since 2002. As Bertrand says,

So it’s an odd time to complain so vociferously about trade imbalance with China since, from America’s standpoint, the trade imbalance is the lowest it’s been in over 20 years.

Nevertheless, the Keynesian/China experts promote and parrot Yellen’s message. Here is a quote from a Western media source:

Against the backdrop of rising international concern, experts believe the manufacturing strategy will not deliver on Beijing’s growth targets. Exports already account for a fifth of GDP, and China’s share of global manufacturing stands at 31 percent. Absent an explosion of demand, they say it is unlikely the rest of the world could soak up China’s exports without shrinking its own manufacturing.

Who are these great experts? The usual suspects.

Michael Pettis tells us that if China goes on expanding its manufacturing exports, it will have to be “accommodated by the rest of the world.” And the rest of the world is unlikely to do that. Really? It seems that China has no problem selling its exports to the rest of the world’s consumers and manufacturers, who are eager to buy.

Another expert is Brad Setser. Setser tells us that “China’s domestic EV market was created via industrial policy; it didn’t appear out of thin air. A critical point, and one that is often now forgotten. Same is true of HSR and wind, and China is trying in other sectors as well.” Shock, horror; it was not achieved through market forces but through state-led investment. He goes on, “The reality that many of China’s export success stories now didn’t originate with the magic of the market no doubt complicates global trade, as adjusting to accommodate China’s successes doesn’t “feel” like a true market adjustment.“ In other words, the U.S. and Europe and Japan cannot compete. So what to do? Setser says, “I think the U.S. should make a real effort to offset China’s economic coercion here. It will take a bit of sacrifice but I at least am willing to step up.” So competition is now called ‘coercion,’ and the U.S. must respond with coercion itself, with Setser ready to help Yellen on that.

The rationality of this nonsense is found in the Western mainstream view that China is stuck in an old model of investment-led export manufacturing and needs to ‘rebalance’ towards a consumer-led domestic economy where the private sector has free rein. China’s weak consumer sector is forcing it to try to export manufacturing ‘over capacity’.

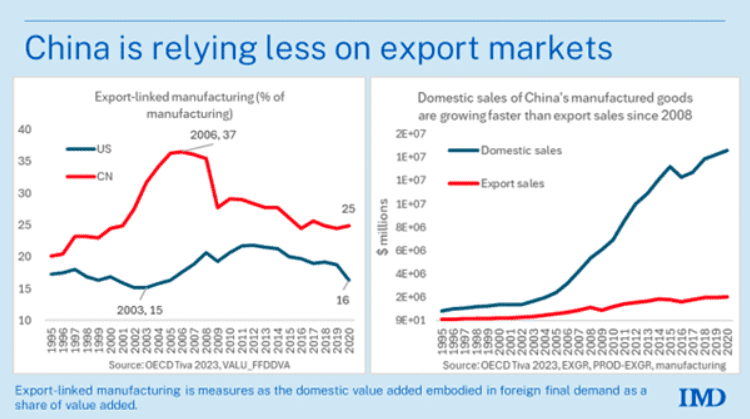

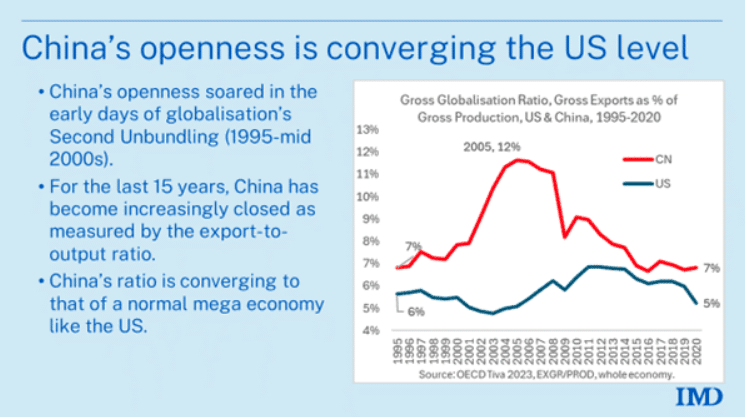

But the evidence for this is not there. According to a recent study by Richard Baldwin, he finds that the export-led model did operate up to 2006, but since then, domestic sales have boomed so that the exports to GDP ratio has actually fallen.

Chinese consumption of Chinese manufactured goods has grown faster than Chinese production for almost two decades. Far from being unable to absorb the production, Chinese domestic consumption of made-in-China goods has grown MUCH faster than the output of China’s manufacturing sector.

Chinese manufacturers remain highly competitive in world markets, despite all the efforts of the West to impose tariffs and other protectionist measures. China is doing particularly well in electric vehicle production, solar energy and other green technologies. But as Baldwin points out, this export success does not mean that China depends on exports for growth. China is growing mainly because of production for the home economy, like the U.S.

But there is a more worrying feature of this ‘overcapacity’ nonsense. It has been swallowed hook, line, and sinker by economists in the Chinese banking sector, who were mainly trained in Western universities. Take the recent speech by the chief economist at the China Bank, Zu Gao. His speech was highly praised by the likes of Pettis and Setser. Xu argued that “the significantly lower consumption-to-GDP ratio in China, compared to the global average, is the fundamental cause of the country’s lackluster domestic demand and economic slowdown.”

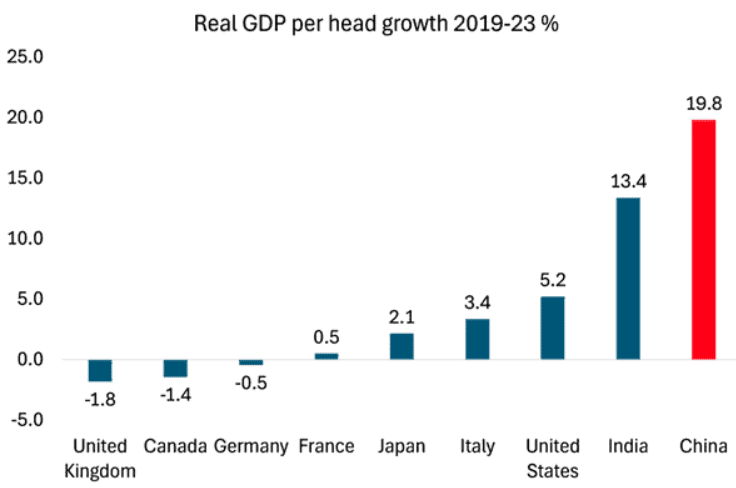

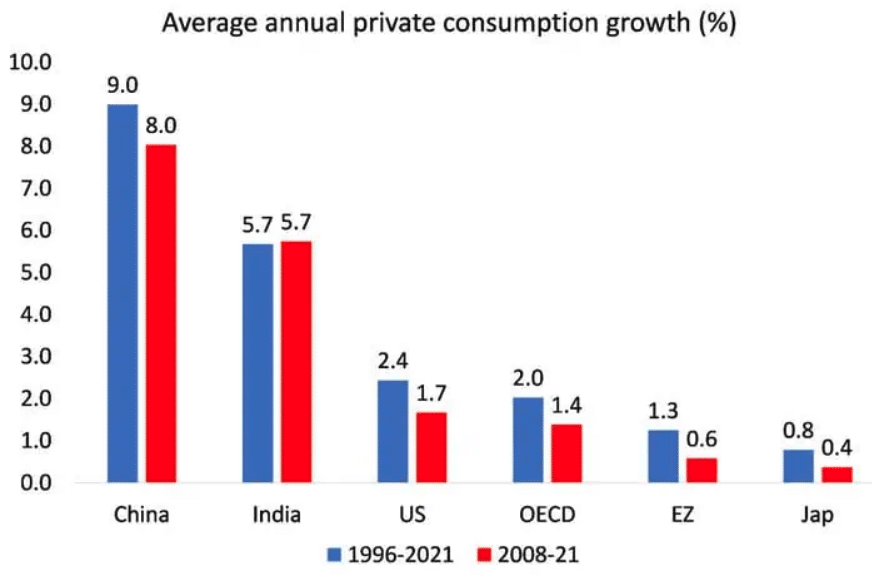

Xu explains that “weak domestic demand, compounded by lackluster external demand or export volumes, results in insufficient total demand, thereby stifling economic growth. In that sense, the long-term growth constraints on the Chinese economy lie not in the supply but in demand.” Really? China’s relative growth slowdown in the past decade has been due to the slowing expansion of its labor force with economic growth then depending primarily on raising the productivity of labor. And that depends on investment in productivity-boosting technology, not consumption, which is a deduction from resources for investment. Moreover, which countries have achieved faster growth in the last few years: the consumer-led West or low-consumption China?

Xu follows up his classic crude Keynesian theory by saying that “the objective of economic growth is to fulfill the people’s expectation for a better life, which is primarily manifested through their expectation for enhanced consumption—better quality food, clothing, and leisure activities. When a country’s consumption constitutes a small fraction of its GDP, it indicates a misalignment between the aggregate economic growth (as depicted by GDP) and the lived experiences of its people.”

But this is just not true. A low consumption-to-GDP ratio does not necessarily mean low consumption growth. And China’s consumption growth has been way faster than the consumer-led economies of the West.

Then we get to the real purpose of Xu’s speech: “The extensive presence of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in China, whose profits and dividends primarily flow to the state rather than households, diminishes the wealth effect that might otherwise stimulate household consumption.” You see, it’s China’s state-led economy that’s the problem: it is stopping “an efficient market mechanism” from working.

So what to do? “Of course, SOEs in China are technically owned by the people, yet their equity is predominantly held by the state. Consequently, the dividends from SOEs primarily flow to the state rather than the households; the profits retained post-dividend distribution from SOEs are not directly connected to the balance sheets of households, making it difficult to contribute to household wealth. So says Xu, “We need to distribute all SOE stocks to citizens,” i.e., privatise the state-owned companies.

The chief economist of China Bank seems to reckon that the only answer to the perceived ‘lack of demand’ and ‘overcapacity’ in China is to restore the dominance of the ‘efficient market mechanism’.