State and Revolution: An Introduction

Lenin’s Big Ideas

Until the Russian revolution in 1917, scientific socialism was most commonly referred to as Marxism. After the revolution, it became Marxism Leninism. Why? What did Lenin contribute that placed him on the level of Karl Marx and his collaborator, Freidrich Engels?

Lenin contributed decisively both to the theory of Marxism and to its practice in the class struggle. Lenin, together with Leon Trotsky, was a decisive leader of the workers’ revolution in Russia in 1917, and the establishment of the first workers’ state in history. Toward the very end of his life Lenin allied with Trotsky once again to resist the takeover of the Communist Party and the new Workers’ state by a flood of opportunists and bureaucrats led by Joseph Stalin.

While the range and depth of Lenin’s contributions was great, this series of articles concentrates on four;

1. the nature of workers’ consciousness and the need for a vanguard party,

2. the evolution of capitalism through monopoly to imperialism,

3. the nature of the capitalist state, and

4. the idea, more fully developed by Trotsky, of the effects of uneven and combined economic and political development on the course of progress in technolog8cally and economically backward countries, the notion of continuous or permanent revolution.

Marxism Leninism is organic. All of these contributions are tightly interwoven with reality and with each other, Understood together, they made possible the successful overthrow of feudalism and capitalism in Russia in 1917 and the ascendancy to power of the workers’ soviets. It turns out you can’t pick and choose among Marxism Leninist ideas any more than you can pick and choose among the ideas of medicine or physics.

The idea that material reality precedes ideas and concepts of that reality is essential. Rather than begin our understanding by sitting in a room and thinking, Marxists begin all understanding of our current situation by gathering and analyzing the factual evidence we see around us in reality and looking for patterns and laws of motion. In this article, we examine Lenin’s profoundly revolutionary understanding of the state as an instrument of ruling class domination

STATE AND REVOLUTION, an introduction

By Gary Porter

EVERY STRUGGLE aiming for genuine and fundamental transformation of society must come to terms with the role of the state.

Today, there is still much debate and controversy about how to approach the state, because these questions are intimately related to how society

can be changed: Can the capitalist state be reformed through elections into something that meets the needs of the majority? Is the state as powerful as it once was or do corporations have more power? Can workers take over the capitalist state or do we need a different one? Is a workers' state a necessity to repel counter-revolution?

It goes without saying that revolutionary socialists, reformists and anarchists have different approaches to these questions. But it is important to test these approaches against the actual experience of the working-class movement historically.

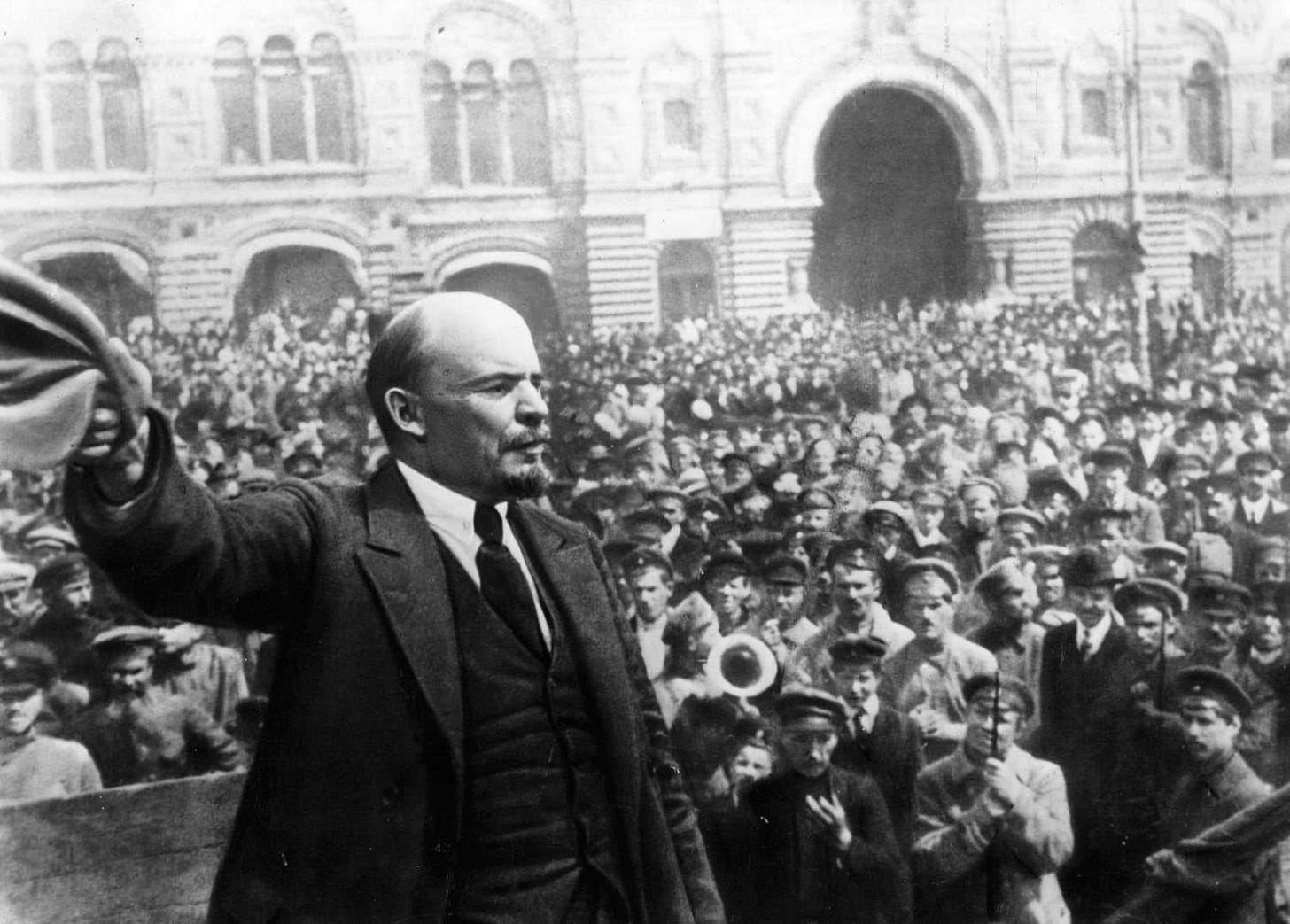

The Russian revolutionary V.I. Lenin wrote what became State and Revolution in the critical months immediately preceding the outbreak of the 1917 February Revolution in Russia. The arguments contained in the short book became a practical guide to Russia's working class in the period before and after the seizure of political power in November 1917.

The capitalist class rules through its monopoly and control over the means of violence in society. The police, the military, the courts and prisons are the essence of the capitalist state and the ruling class uses violence against both other ruling classes in imperialist war and against domestic (the working class) threats to its rule at home.

The notion that socialists could win elections and gradually remove capitalism through legislation had become widespread within the socialist movement before the First World War. Even now, this idea is understandable since we are brought up to believe that the "will of the people" can be expressed through “democratic” elections. When people don't vote we are told they are lazy, stupid or don't care.

But as Lenin put it, using quotes from Engels, "In a democratic republic, Engels continues, 'wealth exercises its power indirectly, but all the more surely,' first, by means of the 'direct corruption of officials' (America); secondly, by means of an 'alliance of the government and the stock exchange' (France and America)."

This picture is familiar today. In a society based on exploitation and oppression, "democracy" is very limited--but, simultaneously, it is used to gain legitimacy for class domination. In any election, the ruling minority's control over the means of production is never up for debate.

Lenin argues that the working class can only liberate itself and humanity through a revolution, something that reformist leaders have "pruned" from Marxism.

Against the idea that socialists could simply and gradually take over the state, Lenin argued, based on the experience of the Paris Commune in 1871, that workers would have to replace the capitalist state machine with a new state, based on institutions of workers' democracy (workers' councils). The capitalist state would not simply "wither away" through successive pieces of legislation. The owners of the means of production, the powerful and wealthy capitalist class, will never permit it.

In support of this argument, Lenin quoted from Engels: "The proletariat seizes state power and turns the means of production into state property to begin with. But thereby, it abolishes itself as the proletariat, abolishes all class distinctions and class antagonisms, and abolishes the state as the state."

However, to defeat the resistance of the bourgeoisie and begin the construction of a new socialist society, the working class needs a workers' state. As Lenin argues:

The theory of the class struggle, applied by Marx to the question of the state and the socialist revolution, leads as a matter of course to the recognition of the political rule of the proletariat, its dictatorship, i.e., of undivided power directly backed by the force of the armed working class.

The overthrow of the bourgeoisie can be achieved only by the proletariat becoming the ruling class, capable of crushing the inevitable and desperate resistance of the bourgeoisie, and of organizing all the working and exploited people for the new economic system.

The proletariat needs state power, a centralized organization of force, an organization of violence, both to crush the resistance of the exploiters and to lead the enormous mass of the population--the peasants, the petty bourgeoisie, the semi-proletarians--in the work of organizing a socialist economy.

Thus, the "dictatorship of the proletariat" would replace the "dictatorship of the capitalists."

WHILE THE reformists denied the need for a revolution that would destroy the power of the exploiters, anarchists, on the other hand, rejected the need for any kind of workers' state. The brutal experience of Stalinist dictatorships has given added life to the argument that all forms of authority and the state need to be opposed and abolished for workers' power to survive.

But how, then, can the counter-revolution be fought? In Russia, the working class took political control over society and over the means of production. In response, there was violent resistance by the expropriated ruling class. It was necessary for the new Russian workers' state to organize a defense of the revolution, to organize the Red Army

This is how Lenin took up the question:

It was solely against this kind of "abolition" of the state that Marx fought in refuting the anarchists! He did not at all oppose the view that the state would disappear when classes disappeared, or that it would be abolished when classes were abolished. What he did oppose was the proposition that workers should renounce the use of arms, organized violence, that is, the state, which is to serve to "crush the resistance of the bourgeoisie."

To prevent the true meaning of his struggle against anarchism from being distorted, Marx expressly emphasized the "revolutionary and transient form" of the state which the proletariat needs. The proletariat needs the state only temporarily. We do not at all differ with the anarchists on the question of the abolition of the state as the aim. We maintain that, to achieve this aim, we must temporarily make use of the instruments, resources and methods of state power against the exploiters, just as the temporary dictatorship of the oppressed class is necessary for the abolition of classes.

However, the workers' state would be very different from those based on minority rule. In State and Revolution, Lenin answers the question of what is to replace the state machine of the old order by referring to the Paris Commune:

The Commune, therefore, appears to have replaced the smashed state machine "only" by fuller democracy: abolition of the standing army; all officials to be elected and subject to recall. But as a matter of fact, this "only" signifies a gigantic replacement of certain institutions by other institutions of a fundamentally different type. This is exactly a case of "quantity being transformed into quality"...

The organ of suppression, however, is here the majority of the population, and not a minority, as was always the case under slavery, serfdom and wage slavery. And since the majority of people itself suppresses its oppressors, a "special force" of suppression is no longer necessary! In this sense, the state begins to wither away.

Like Marx and Engels, Lenin never attempted to set out a blueprint for what a future socialist society would look like. However, State and Revolution contains a very important discussion of the transition from capitalism to communism.

Lenin believed it would be impossible to say exactly when the state would ultimately disappear, but that it would be a lengthy, drawn-out process and a struggle. A new society must emerge out of capitalism and will be marked in all respects by birthmarks from the old society--economically, morally and intellectually. For human beings to fully free themselves from the marks of class society will take generations.

But society will become progressively more equal, and democracy will become fully meaningful, when more and more people take direct control over the running of society. The continual expansion of the means of production will end the material basis for competition, fear and want.

To explain the higher phase of communist society, Lenin quotes Marx:

In a higher phase of communist society, after the enslaving subordination of the individual division of labor, and with it also the antithesis between mental and physical labor, has vanished, after labor has become not only a livelihood but life's prime want, after the productive forces have increased with the all-around development of the individual, and all the springs of the cooperative wealth flow--only then can the narrow horizon of bourgeois law be crossed in its entirety and society inscribe on its banners: From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs!

In State and Revolution. Lenin synthesizes many aspects of Marxist theory with a brilliant grasp of the dialectical method to make a powerful case for revolutionary socialism. It should be required reading for all revolutionary socialists.

QUESTIONS

What are the causes of the rise of bureaucracy in trade unions ? In the NDP?

What are the preconditions for the final defeat of bureaucracy?

Is communism inevitable?

Many people argue that the greed, envy and violence are inevitable, part of human nature. Therefore, the society to protect itself will always need a state, an organization of violent repression of the dark side of human nature. To think otherwise it not materialist, but utopian. How do communists respond to this view?